Special feature post for World Wetlands Day, February 2nd. Click here for more information about IWMI's work on wetlands.

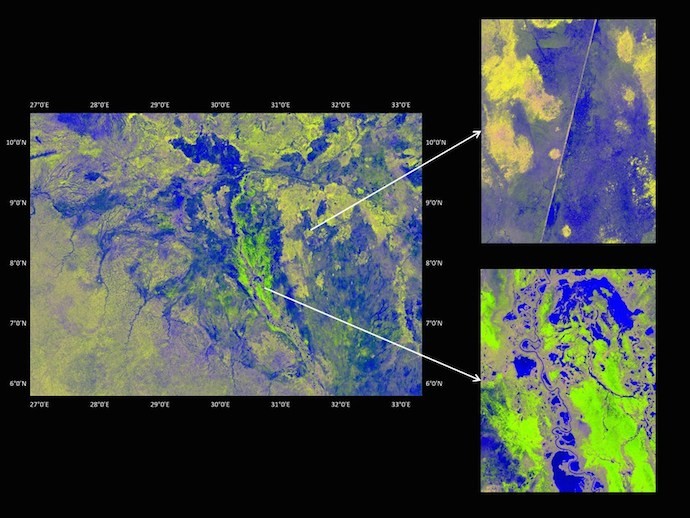

First maps of the Sudd derived using radar remote sensing showing how flooding patterns change over time.

Satellite images based on synthetic aperture radar are enabling researchers to see water distribution in the wet-season Sudd for the first time. Photo: JAXA

Satellite images based on synthetic aperture radar are enabling researchers to see water distribution in the wet-season Sudd for the first time. Photo: JAXAThe Sudd wetland of South Sudan is one of the largest tropical wetlands in the world. However, despite covering an area twice the size of Spain in the wet season, very little is known about the number of people it supports or the current state of its biodiversity. “The wetland as a whole and its dynamics have not been mapped repetitively or systematically,” explains Lisa-Maria Rebelo, a researcher in remote sensing at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and a member of the international science team set up to support the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (Jaxa) Kyoto and Carbon (K&C) Initiative. In part this is due to the fact that satellite images relying in visual data cannot easily see beneath vegetation or clouds to get an accurate picture of where the water is.

Through the K&C initiative, however, Rebelo is working to create the most up-to-date map of the Sudd using radar remote sensing data supplied by JAXA. The long-wave band radar data acquired by the PALSAR instrument between 2006-2011 has the benefit of allowing scientists to see what’s happening beneath the vegetation canopy. “We get a very distinct signal between open water, flooded vegetation and terrestrial land,” says Rebelo. “This gives us a much clearer picture, compared to optical data, for looking at the dynamics of the different wetland components, and inundation patterns and dynamics.”

A giant sponge

The Sudd, of which 57 million hectares was designated a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance in 2006, is located in the lower reaches of the White Nile (Bahr el Jebel), which flows north from Lake Victoria in Uganda. The wetland receives rainfall from the surrounding catchment and in-flows from Lake Victoria. It acts like a giant sponge, retaining water and releasing it slowly throughout the year. In this way, it regulates the flows of the White Nile. Early findings from Rebelo's analyses of the satellite data show the wetland has increased in size on an annual basis over the past ten years. This does not appear to be due to changes in rainfall patterns, so therefore must be related to changes in flow; however, more work is needed to find the exact reason.

Papyrus, aquatic grasses and water hyacinth, inhabited by crocodiles and hippopotamuses, grow in dense thickets in the shallow waters of the Sudd. Floating islands of vegetation up to 30km across make it hard to navigate a way through the swamps either by boat or overland; early explorers seeking the source of the Nile often took months to get across. Two civil wars, the first between 1955 and 1972 and the second from 1983 to 2005 have also contributed to the dearth of knowledge about the Sudd. The political instability culminated with South Sudan becoming an independent state in 2011, but gaining access to the wetland remains difficult.

Cultural roots

In April 2010, Rebelo and a team of IWMI researchers met in Juba, the main town at the southern end of the wetland. The aim was to find out what people thought of the wetland, the main threats to the wetland, and the priorities for future research. It became apparent during the workshop that the wetland was of great cultural importance to many South Sudanese. ”Representatives present from the Government of South Sudan were all very passionate about the wetland,” Rebelo recalls. “Many of the people we met had grown up in or around the wetland and many of their cultural ceremonies were tied to it.”

Shoebill Stork. Photo: Mark Jordahl on Flickr

Shoebill Stork. Photo: Mark Jordahl on FlickrAn environmental hotspot

The few studies that have been conducted on the wetland reveal the Sudd to be a unique and highly biodiverse ecosystem, home to over 400 bird and 100 mammal species. The Sudd supports the highest population of shoebill storks and the greatest numbers of antelopes in Africa. Many fish species migrate from the surrounding rivers to the nutrient-rich floodplains to feed and breed during the seasonal floods. While no recent figures are available, the Sudd is of great importance to local livelihoods. Beyond the wetland lies a very hostile, arid environment. The nomadic tribes move with the floods, relying on the waters to graze and water their cattle or provide fish.

Despite the wetland’s value, it faces a number of threats. In the 1980s, a 260km stretch of a planned 360km canal was dug, with the aim of diverting 4.7 billion cubic meters of water annually to Egypt and Sudan for irrigation. The project was halted by the civil war but if re-instigated could have drastic environmental consequences. Various dams are presently planned upstream of the Sudd, which could also affect its seasonal water flows. And with the recent discovery of hydrocarbons in the region, oil exploration is under way. “Drilling is already under way but there are no regulations in place and no monitoring of pollution,” says Rebelo. “With the on-going difficulties in gaining access to monitor and assess the current status of the wetland and changes within it, it’s even more important to generate the information needed using the satellite data.”

Resources

Source: Flood Pulsing in the Sudd Wetland: Analysis of Seasonal Variations in Inundation and Evaporation in South Sudan

IWMI resources on wetlands

Comments

i don't "see" anything.

Hi Pauly - thanks for letting us know. The image has been restored.