Today I was asked to comment on the terms of reference for a new communication position in our program. It focused on preparing articles, editing science, writing for the web and preparing press releases. For what purpose and for whom, I am not sure.

Creator: Camilla Zanzanaini

Creator: Camilla ZanzanainiIn parallel with this, there has been a long discussion within communication circles regarding how we work with Public Relations (PR) firms, what makes good PR, what types of headlines we can or cannot write and the associated “ditchwater” affect of having too many people comment on communication pieces.

Scientists are being asked to change, to ensure their research leads to concrete outcomes. As communicators, I wonder if we have really reflected on what needs to change within our own work to support this push towards outcome-based research?

With our limited resources, are we spending too much time on logos, press releases and PR at the expense of helping our research achieve greater impact? Are we ourselves marginalizing our own role in this process?

I think communications can be more than that. There are a number of great initiatives that are already breaking down these stereotypes. Many programs are beginning to develop strategically produced materials and communication processes that help reach different clients (farmers, policy makers, development professionals, investors) that we hope to influence and engage with.

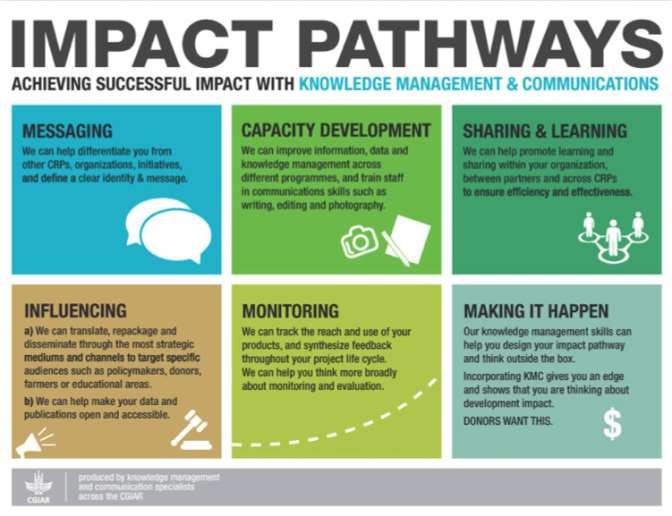

At a recent Knowledge Management and Communication Workshop, we focused on reorienting our work from corporate and administrative activities, towards ways to help researchers achieve outcomes and impact. Some areas of expertise and skills that we can provide are illustrated in the infographic above.

Spurring on the climate change discussion

Our research focuses on many global issues, climate change being one that is always a hot topic. But does everyone have access to or even know the most accurate and up-to-date information? The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) has invested a lot of time and energy to get the facts right and help spur on the discussion regarding climate change and agriculture. I heard one project leader say it was like ‘giving birth’. And what an amazing child it is!

The website, graphics and information is presented in an artistic and visually-stimulating way. The complexity and uncertainty of climate science is captured and rendered in easy-to-understand infographics. Here we don't need to ‘sell’ or spin the work to make it interesting, as the information and style of communication speaks directly to a range of clients whether they be students, businessmen, investors or academics.

Proving before investing

Now here is a novel idea – rather than investing tons of resources into a project before understanding if it will work or not, why not develop a proof of concept first? That is what the Ecosystems Services team from Bioversity International did. Working with students from the University of Idaho in consultation with game design experts, they developed a step-by-step game design that is ready to be turned into a full role-playing video game.

This is a serious game about ecosystem services. The intention is to raise awareness and teach players about integrated landscape management and ecosystem services in a fun and interactive way. By making choices, observing outcomes and adjusting strategy, players will learn how to maximize benefits from specific ecosystem services using different management tactics. They are now looking for a start-up fund but have the base ready to get potential funders and partners interested.

Repackaging science into usable materials

In the Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF), we have been moving towards transforming science into materials for our clients. One of the first materials created was a beautifully rendered manual on livelihoods and land use planning. Rather than focusing solely on a scientific output, the project decided to produce a manual for district field workers and professionals who can really put our research to use.

At the recent CPWF Mekong Forum, a wide-range of materials was presented as outputs of research – not just stuffy posters and academic presentations, but video lectures, participatory videos, manuals and community-based materials. Communications offers an extensive toolbox that can be tailored to different needs and audiences.

Finally, rather than write another scientific book (which we have also done of course!), CPWF repackaged the science of more than 70 projects into materials for students, teachers and development professionals. A set of “water dialogue posters” helps place water and food issues into perspective. Each poster is designed for brevity, clarity, and accessibility of message. At the same time, each poster is backed up by in-depth research which you can access through an accompanying documentation box, or the CPWF sourcebook – a collection of articles that provide concise information on how, why, and where such methodologies, approaches, and tools have worked in the past and may work in the future. Weighing almost 2kgs, the sourcebook serves multiple purposes, including exercise!

There are many ways that communicators can play a role in helping scientists come down from their ivory towers to engage and produce science that is more relevant to society. But this is not just a challenge for them, we as communicators also have to move beyond our comfort zone and produce materials that are socially relevant.

Comment and let us know : What innovative communications tools are you using to repackage science into usable materials? What are other ways that we can make science more socially relevant?

/index.jpg?itok=EzuBHOXY&c=feafd7f5ab7d60c363652d23929d0aee)

Comments

Great post and great initiatives!

To share some further ideas on how we've repackaged science (or complemented it with 'farmer science') in a couple of projects:

In the Nile Basin Development Challenge (one of the Basins that formed part of the CPWF) we have been using:

- Participatory video (https://nilebdc.org/?s=participatory+video)

- Games (on strategic use of natural resources) e.g. Wat-A-Game (adapted with AfroMaison partners from the original W-A-G) and proprietary 'Happy Strategies' game: https://nilebdc.org/?s=game

- We piloted a VIP dinner at the end of the program to present our key messages and further develop our relationships with key decision-makers and partners. During that dinner we presented our eight key messages in various ways (video, audio, Powerpoint, digital story etc.) https://nilebdc.org/2013/11/19/nbdc-closing/

- Digital stories (https://nilebdc.org/2013/02/10/digital-stories/)

In Africa RISING:

- We have been using storytelling and photo-journalism trips to gather testimonies from farmers about their strategies with sustainable intensification and to illustrate program work in the regions where we are active: a.o. https://africa-rising.net/2013/12/18/cps-ghana3/ and https://africa-rising.net/2014/02/06/cps-ghana4/

- We are currently working on a possibly interactive visual to depict the complexity of sustainable intensification and whole farming systems.

In the Climate Change Social Learning initiative of CCAFS (more about this at: https://ccsl.wikispaces.com/) we have developed a whiteboard video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pKaoD5sGjw) a la RSA Works, to attract attention to the set of issues we are working on. In that initiative we are generally turning the research as part of other activities, through a broad 'social learning' approach that engages all partners and parties concerned - we believe a very hopeful (if not brand-new)

And, although there is nothing unheard of in this, across all these projects we also make strategic use of events for interactive conversations that challenge our science and the way we share it with other people...

All these examples are a good testimony that CGIAR centres, research programs and partners are looking for alternative, more engaging and more effective ways to make sure that science is developed with a careful eye for its use and for the relationships that need to be built along the way in order for that to happen!

Again, many thanks for your great post!

Thanks Ewen for sharing these fantastic resources with us!

On the blog we are also working on making strategic use of events by connecting "themed months" (such as our Ecosystem Services month https://wle.cgiar.org/blogs/tag/essmonth/ and Landscapes month https://wle.cgiar.org/blogs/tag/landmonth/) with related events (such as the Ecosystem Services Partnership conference and the Global Landscapes Forum).

This has exponentially increased our blog readership and has helped us connect a more targeted audience with relevant materials and information.

Very good article, Michael and Camilla. You capture the real challenges and also the exciting opportunities we face in communicating complex research. Thanks for linking to the Big Facts website. It's an example of a 'big idea' made possible through combined efforts of the science and communication teams, and hopefully a template for future initiatives!

A great post with valuable strategies for improving science communication.

The principle of testing before investing is absolutely critical. At the USDA National Agroforestry Center (https://nac.unl.edu/ ), we prepare mock-ups of our tools and evaluate them with end-users before proceeding. This has been invaluable in developing tools that meet client needs such as:

CanVis: a visual simulation software program for depicting photo-realistic conservation alternatives

https://nac.unl.edu/simulation/products.htm

Conservation Buffers: Design Guidelines for Buffers, Corridors, and Greenways

https://nac.unl.edu/buffers/

Repacking science into usable information is essential. Some of the challenges facing science communication include:

Scientific information is widely dispersed and practitioners may not have the time to seek out these scattered resources

Unless a synthesis of the science is completed, practitioners are left with the daunting task of reviewing and assembling the numerous studies into a meaningful whole

With the shift towards managing landscapes for multifunctionality, practitioners need information that covers a broad range of functions.

To manage for multiple functions, practitioners need to understand, use, and communicate scientific information from many ecological, social, and economic disciplines.

We tried to address these challenges by developing the Conservation Buffers guide which synthesized over 1,400 research publications into illustrated design guidelines. Because understanding and use of information is often negatively related to the perceived complexity of the information, we used a variety of science delivery strategies to manage and present the information in a clear and concise format.

I would also like to add an additional strategy which is a follow-up evaluation of tool use by clients.

Too often this is not done and we do not learn what really works and what didn't work. Although we involved clients in the development of the Conservation Buffers guide, we conducted a survey of clients after they had used the guide for a year. We learned some valuable lessons. To complete the circle, we are publishing the results of this survey so others can learn from them as well.

Cheers,

I think that science can best be made relevant through the "knowledge translation" concept. KT is more than generic communication because as you know, the major chunk of research knowledge remains with the researcher. When you apply KT concept, you explore best options of translating or transferring that knowledge to people who will practically apply it without diluting its content. KT in short is the middle meeting ground between two fundamentally different processes: those of research and those of action. You first establish the profile of users of the research knowledge; what action they should undertake and how they should best access and comprehend the body of research knowledge; you also establish benchmarks and how much has been achieved when the actors apply the research knowledge. This in my view will make science relevant.