A version of this op-ed was published by The Conversation.

Healthy soils are vital to meeting food security, nutrition and climate change goals, but about 40 percent of soils in sub-Saharan Africa are of poor quality. New technology can help us quickly and cheaply diagnose soil health troubles – where, what and why – and set us on the path toward successful treatment.

While close to half of all soil in sub-Saharan Africa is already of poor quality, the outlook is even grimmer. It has been estimated that more than 65 percent of Africa’s fertile, productive soil is in decline, soon to be lost if desertification and degradation continue.

The impact of land and soil degradation is especially severe in countries like Ethiopia, where smallholders struggle to grow staple food – such as teff, wheat, maize, sorghum, and barley – and eke out a living.

Here, soil health has been declining due to unsustainable farming practices, animals grazing on large patches of land and trees being felled for fuelwood. Furthermore, state ownership of all land in Ethiopia means that farmers are insecure about their tenure and less inclined to invest in the land’s health.

Why soil health matters

Treating degraded or starved soils is important. Healthy, more nutritious soil means that farmers can grow a greater variety of crops, giving them more diverse, nutritious diets. It also puts an end to the vicious cycle of over-use and degradation; when soil is healthy, farmers no longer need to expand onto previously untouched land as when their original plots become exhausted.

But it is not only about increasing productivity and growing more food. Healthy lands also contribute to social and political stability, decreasing the risk of conflict and migration. What’s more, sustainable land management practices can increase soil’s capacity to store organic carbon, thus helping to mitigate climate change by absorbing carbon from the atmosphere. In other words, healthy soils are a prerequisite to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and realizing the ambitions of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

To better understand what it would take to restore soil health in Ethiopia, we set out to get to know the country's soil.

Diagnosing soil health

The first step toward diagnosing soil health was to understand what’s wrong. Soil spectroscopy – a new, light-based technology – makes it easy, fast and cheap to analyze very large numbers of soil samples.

By measuring how infrared light at different frequencies is absorbed by a soil sample, we get a snapshot of the soil’s organic and mineral contents. It is this combination of organic and mineral material that determines how healthy or unhealthy soil is – for example whether it is able to retain water, store carbon and resist erosion.

In Ethiopia, the Soil-Plant Spectral Diagnostics Laboratory has gathered more than 100,000 soil samples from all over the country. This effort is part of the work we are doing in support of the Ethiopia Soil Information Service (EthioSiS), established with help from World Agroforestry and the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE).

The lab analyses have confirmed that the health and fertility of soil varies across Ethiopia. We now know that 96 percent of soils are either acidic or alkaline – this affects the nutrient levels in soils because a neutral pH is desirable.

The data has also corrected some misconceptions: for example, analyses have shown that soils in some parts of the country are lacking potassium, despite previous beliefs that this nutrient was generally abundant. Potassium encourages plants to grow healthily, and is particularly important for plants that store large amounts of sugar and starch – such as potatoes.

Soil property maps to the rescue

We have used all of this collected soil data to create soil property maps, which show where soil fertility issues exist and whether (and which) nutrients are missing. With this information, decision makers, such as extension officers, can help farmers decide where to restore and better manage soil as well as where, what kind and how much fertilizer to use.

So far, soil fertility status and fertilizer recommendation atlases have been published and handed over to the Amhara, Harari, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region, Tigray regions and Dire Dawa administration. Maps for 300 woredas (districts) of Oromia regional state and the Benishangul-Gumuz and Gambella regions were also completed. The Afar and Somali regional state maps are under production.

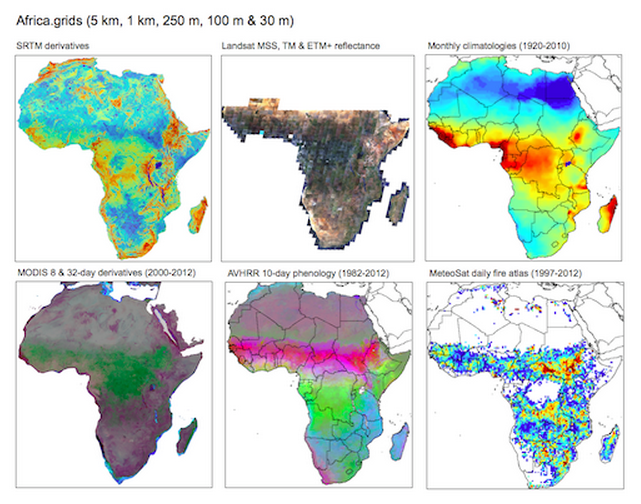

Ethiopia's not the only African country doing this. It’s part a continent-wide effort to gather and analyze soil data under what we call the Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS). Tanzania, Ghana and Nigeria have all worked with AfSIS to develop their soil information systems, conducting nation-wide soil health surveys and developing digital soil resource maps for targeting interventions like sustainable land management practices.

More African countries could follow suit, but they lack resources, notably manpower. Capital investment in this technology is also a constraint, so is how to make decisions based on data coming out of this technology.

But it's worth the investment. Governments can use the maps to better target sustainable land management interventions, and smallholder farmers can consult them to make informed decisions on improving their soils.

The ultimate aim is to arm thousands of African farmers with the exact insights that will help them fight soil and land degradation.

Thrive blog is a space for independent thought and aims to stimulate discussion among sustainable agriculture researchers and the public. Blogs are facilitated by the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) but reflect the opinions and information of the authors only and not necessarily those of WLE and its donors or partners. WLE and partners are supported by CGIAR Trust Fund Contributors, including: ACIAR, DFID, DGIS, SDC, and others.