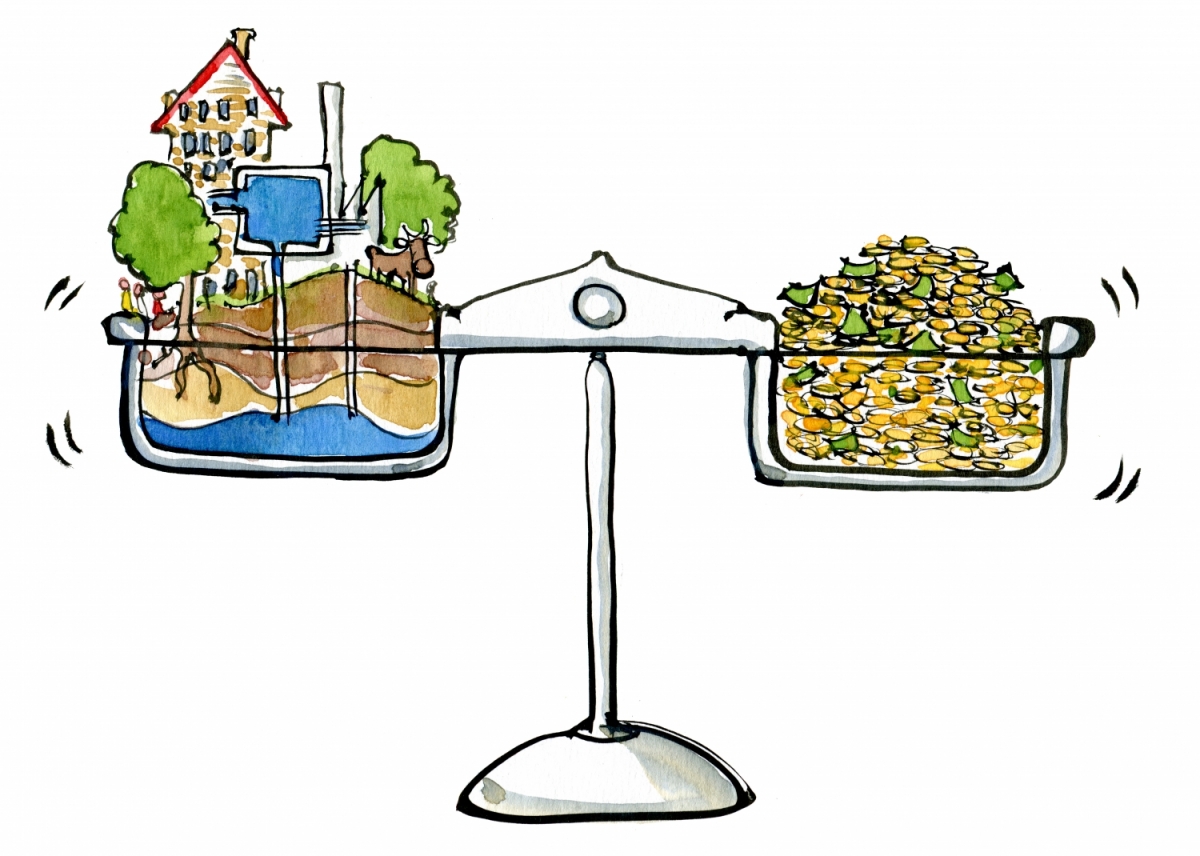

The ‘Global Landscape Forum – the Investment Case’ convened in London earlier this month with the aim of mitigating climate change and reducing poverty through investments in landscape restoration. Events like this one are desperately needed to ensure private-sector involvement in conservation efforts: a 2014-report found that $200-300 billion of investment per year is needed to meet the global need for conservation funding. This means that investments need to be at least 20-30 times greater than what they are today.

What are the barriers to bridging this gap? And what questions still remain to be answered? Panelists and participants in a World Bank-led session on ‘Risk reduction measures for private sector investment in landscape restoration’ identified a number of challenges:

Main barriers to investment in landscapes by the private sector #ThinkLandscape @GlobalLF @WorldBank pic.twitter.com/D8znhxM0aG

— Monica Ortiz (@amdortiz) June 6, 2016

- Weak, contradictory or non-existing policy frameworks hamper investments in landscapes. Panelist Triyanto Fitriyardi, of the International Finance Corporation, pointed out that especially the private sector is likely to shy away from investments in countries where national policies lack clarity or frequently change.

- Relatedly, weak land rights and tenure in countries where the need for landscape restoration is greatest adds complexity. Whereas clear and uncontested land rights lend themselves well to good stewardship of landscapes, uncertainties on land ownership leads to land degradation and deforestation.

- Uncertain and unquantifiable risks also represent a well-known challenge. Panelist Stephen Rumsey, of Permian Global, an investment firm dedicated to the recovery of forests, pointed out that as long as we have no data on and no ways to measure the consequences and impacts of landscape investments, then the private sector is likely to remain largely disinterested.

- An inherent conflict between the typically short-term interest of the private sector and the long-term timelines of landscape investments also exists. This challenge is also related to the question of scale: large-scale landscape restoration projects take more time than private sector investors are typically willing to commit.

- Finally, even if the challenges listed above were overcome, participants agreed that there is a basic lack of shovel-ready projects for the private sector to invest in.

Possible solutions

Attendees proposed a handful of mechanisms to address these issues.

Paola Agostini, of the World Bank, pinpointed multi-stakeholder initiatives as key to facilitating landscape restoration. Whereas national governments are unlikely to be able to provide the level of financing needed, they do hold the long-term perspective and tools necessary to facilitate successful projects and must therefore be included in the landscape restoration process. Involving government actors is crucial to reach compromises that take into account both the private sector’s commercial interests and the public sector’s restoration visions.

In some cases, the private sector may take the lead. In Brazil, for example, a private company has taken the initiative to plant more than 7.2 million native trees in the past 8 years to restore forested land (see p. 6-7). This type of project is dependent on finding investors that have both the cash and interest to take a long-term perspective. It also, of course, raises questions about the consequences of leaving the restoration of common-pool resources in the hands of the private sector.

Establishing multi-stakeholder funds seems to be emerging as a mechanism for facilitating collaboration between governments, private sector and other actors. During the event in London, the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund was pitched as a way to unlock capital for scaling up land restoration globally. At the regional level, similar funds are already operating, such as in Kenya, where Africa’s first water fund was launched in 2015.

Unanswered questions

Perhaps most interesting, and most challenging, were the unanswered questions that the event unearthed.

Among them is how landscape restoration supporters can better engage with the private sector. Toward the end of the session on risk reduction measures, a participant representing a major consumer brand stood up to address the panel of experts. Her question was simple enough: how does any of what you are discussing here help me?

And despite the fact that she outlined her brand’s priorities quite clearly – meeting consumer demand in terms of brand image, securing their supply and value chain, and meeting and reporting on corporate environmental, social and governance goals – no one on the panel was able to give a full answer to her question. Incentivizing the private sector to invest in landscapes has to start with presenting a compelling business case.

.@GlobalLF closing session: The wave has broken - interest in green finance is huge. Now need to find ways to capitalize. #InvestLandscape

— WaterLandEcosystems (@WLE_CGIAR) June 6, 2016

Another tricky question from the floor went largely unanswered: Natural forest, for example, is one of the most beneficial kinds of restoration projects in terms of climate change mitigation, ecosystem services, and value for local communities. However, such projects are not attractive to the private sector because there is only a limited financial return on investments. So does that mean that engaging the private sector will imply compromising on restoration objectives?

Who will take the lead?

Finally, several discussions during the event focused on who could or should take the lead on facilitating landscape restoration initiatives. As one participant commented, brokering collaboration on complex land restoration projects and among stakeholders with contradictory needs and interests is not easily done, and such efforts require time and money.

So, while it is obvious that there is a need for intermediary institutions or actors to connect big money with often small-scale restoration initiatives, there are not a lot of obvious contenders for this role.

This might, however, be where research institutions such as CGIAR could play a role: For example, CGIAR recently offered to host the new 4pour1000 initiative, which seeks to mitigate climate change through soil carbon sequestration.

Taking on such responsibilities, to facilitate collaboration among diverse stakeholders, might place CGIAR in a position to make a real difference on landscape restoration. Yet, it remains to be seen whether CGIAR - or other similar institutions -have or can mobilize the skills and resources required to take the lead on brokering large-scale landscape restoration initiatives.

Watch: GLF – The Investment Case: “We need courage to go outside our comfort zones”

/index.jpg?itok=EzuBHOXY&c=feafd7f5ab7d60c363652d23929d0aee)

Comments

Thanks Marianne for this thought-provoking summary of the GLF day in London! I think that properly enhancing landscape sustainability requires identifying co-benefits for all stakeholders - in this case land owners, private investors, governments and smallholders whose land tenure is often weak or inexistant. Any stakeholder willing to "take the lead" on this will not only need to have convening power but also hold a capacity to identify and measure such co-benefits. Rightly what CGIAR is trying to achieve with the 4pour1000 initiative which not only seeks to mitigate climate change, but also to make farming systems more resilient to climate change and more food secure - genuine co-benefits expected from soil carbon sequestration in agriculture and forests.

Thank you, Alain, for your thoughts on this -- and for adding a few more words on the 4pour1000 initiative, which indeed illustrate your point on co-benefits. I agree that anyone 'taking the lead' will need convening power and the ability to identify and facilitate sharing of (co-)benefits, but as discussions in London reflected, shouldering such a responsibility requires time and money, so having resources and incentive to invest them in facilitating such initiatives are, I believe, also requirements.